Today is Day of DH! All Digital Humanists in the world are invited to share online the chronicle of their day, contributing to answer the question which all people dealing with Digital Humanities is asked all the time: “What do you do as Digital Humanist?”

Honestly, during my MA I was asking to myself this question very often, especially during my first year: I guess because DH means A LOT of things, and when approaching this field one needs to find a personal path, remaining at the same time flexible and open to other researches.

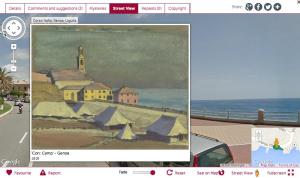

When I decided to start my MA, I was hooked by the multidisciplinary approach necessary to study DH, which in some way reflected the different directions I was taking at that time: I studied Archaeology at the University, but in the following years I worked more as a videographer than as an archaeologist. I’ve always found that these two apparently incompatible professions could be linked, as I love documentaries and especially the ones with an historical subject. But I noticed that very rarely television and cinema manage to engage constructively the audience about these themes, and I think the cause of that is a gap in the communication between professionals and amateurs which still needs to be bridged.

I think community archaeology and history projects can be a good starting point to deal with that, but also that more research on the dynamics of public engagement is needed to address these communication issues.

In my dissertation I would like to analyze how the public gets involved nowadays regarding archaeological themes, focusing on the comments posted by users on posts from the British Museum’s blog, the Daily Mail online (selecting the news about archaeology) and the History Channel Facebook page, reflecting also on how different institutions (museums, press, tv) handle social media tools in order to reach a wider audience.

I hope the comments will allow me to measure the level of popularity of posts and the level of engagement of the public, highlighting at the same time users’ preferences and their relationships and connections with other users.

So, that’s what Digital Humanities can (also) be: a field of research which, using knowledge from humanistic and scientific fields, aims to find new ways to communicate and engage the general public about cultural themes, for the benefit both of professionals and amateurs.